We've begun the

Tobira textbook, and I'm finding it at once easier and more difficult than the

Genki books. The first lesson is on the basics of Japan itself—islands, cities, particles, etc.—which I don't think

Genki covered at all. (先生 says Oosaka leadership wants to change the city's particle from 府, prefecture, to 都, capital—a particle currently enjoyed only by Toukyou itself! Kyouto is the only other 府. But apparently the people don't like the sound of Oosaka-to much less than Oosaka-fu. Politics of language!)

Tobira also is much more kanji-dense, so it's a more difficult read, but it'll be good for me.

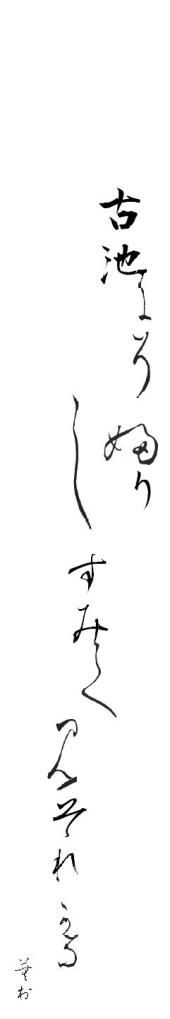

In 習字 we've begun writing winter haiku, and we got far enough with it last time to start working on placement of lines on the page (chirashi or tanzaku style). Because I need practice with both chirashi "theory" and reading/kanji, over the holiday break I've been working on 仮名精習, that amazing book of kana and chirashi theory, and pulling out any kanji/vocab I don't know. So, I think I'll end up with a very specific vocabulary.... 例えば、

- 方向 houkou, direction (eg, of a line, or differentiating slightly in the directions of two lines)

- ぬく nuku, a mysterious one that's usually in kana and seems to mean (sometimes) lifting the brush off the paper (eg, omitting it) or (sometimes) pulling one line out a bit past another (eg, extruding) 抜く, 貫く (ぬき筆)

- 転折 tensetsu, a sudden turn (of the brush, as from horizontal downward)

- 対向する taikou suru, "reverse direction", which seems to equate to gyakuhitsu 逆

and, my favorite so far,

- 気脈 (kimyaku): "conspiracy / secret communication"—in this case, lines within a character that should connect continuously even when the brush isn't touching the paper

逆 is an interesting kanji. The radical is shinnyuu, walking/advancing (or a path or road, as in 道 or 通る), but funnily enough not used in 歩く. But the つくり is 屰, "disobedient", with similar meanings of reverse/inverse, a sense of going against the grain. Both carry readings of ギャク and さか・らう. As you might suspect, only one (逆) is still in general use. That radical itself doesn't seem to unite other kanji, but it does seem that that + 欠 "lack" + 厂 "cliff" appear together with some frequency. The meanings don't seem to unite much, but most have ケ-like readings. I'll have to check some of them out in Henshall.

There also are some kanji pairs that keep coming up and mean opposites—the lightness/darkness, thickness/thinness, etc., of lines. For most of them I know at least one of the kanji (or, at least, its kun'yomi) and can guess the other. Tough going, but worth it!