In shuuji we've been writing tanka and haiku by some of the great

poets, so recently we've also been practicing reading (ie, deciphering)

poems handwritten with hentaigana

in addition to kanji and kana. すごく難しいと思いますけど、頑張っています。When I get home I

try to google them, to read up on the poets and their context.

This is one of my favorites so far:

袖ひちて

むすびし水の

こほれるを

春立つ今日の

風やとくらむ

sode hichite (浸?)

musubishi mizu no

kooreru o

haru tatsu kyou no

kaze ya tokuramu

Soaking my long sleeves,

I took up in my cupped hands

waters that later froze.

And today, as spring begins,

will they be melting in the wind?

(Steven Carter's translation)

On this first spring day,

might warm breezes be melting

the frozen waters

I scooped up, cupping my hands

and letting my sleeves soak ("hijite") through?

(Helen Craig McCullough's translation)

Interesting differences. "Diagramming" as one would do with an

English sentence probably wouldn't be fruitful, but the grammar seems to

go like this:

subject: kaze, wind

what kind of wind? harutatsu kyou no—of today, the start of spring

object: kooreru, frozenness

frozenness of what? mizu, water

what kind of water? musubishi, scooped

what kind of scooped? sode hichite, sleeve-soaking

verb: tokuramu, (questioning) melt

So—will the breezes of today, the first day of spring, melt the

now-frozen water that (I) (earlier) scooped (with cupped hands), soaking

my sleeve(s) in the process?

Interesting play of

meanings, too, between musubu and toku(ramu). Originally when we read

this I thought musubu meant to tie; maybe it was that sode had given me

the image of kimono and obi (musubi, the knot in the obi). But it also

has the sense of joining hands together, as when scooping water. Toku

can mean melting or dissolving (「湖の氷は解けて。。。」), but it can also be (with

various kanji) untying, untangling, etc. We also have kooreru (to

freeze) nominalized by を, as also happens with aru in the tanka we're

doing now (「久しくも。。。」); 先生 tells me the の is commonly omitted in

classical poems.

Anyway. I like it because it makes me think of the tsukubai, the

basin outside a tearoom by which one stoops to "wash" (purify) one's

hands and mouth. What does one do in the winter, when the water's frozen?

This would be fun to write someday, to hang up for tea at the start of spring.

Wednesday, July 25, 2012

Tatami layout; Art Museum teahouse; acquisitions.

A thing that's good about having chanoyu class so far away in the

northwest of the city is that the walk home (a bit under 5 miles) takes

me past all kinds of interesting things. So, after tea I like to wander

wherever I feel like wandering. I often head toward the Philadelphia Museum of Art; the collection is so vast, and so diverse,

that I always encounter at least one piece there that says to me whatever I need to hear that day.

This past Saturday, when once again I found myself at the PMA, I had two things on my mind: tea utensils (道具 dougu) and tearoom tatami layouts. Dougu, because I always think about dougu after tea; after hours of handling them and discussing them (during 拝見) it's impossible not to. Tatami configurations, because we'd just had our first class in the new Sakura Pavilion*, in which the tatami for tea practice are configured differently from the practice spaces at Shofuso itself.

At Shofuso we practice either in the shoin, a 15-mat room, or in the small chashitsu, a square format that's 4.5 mats in overall size but with an inset tokonoma that occupies one half mat in one corner. (See image at right; said to reflect the tearoom in which Rikyuu ended his life, which presumably was at Juurakudai.) The Sakura pavilion has loose tatami that can be configured however the teachers think best, so this time it was a standard four-and-a-half-mat format (below). Of course, since pretty much everything (including every step) in chanoyu is choreographed per the configuration of the tatami, the new format means recalibrating every step! Like migrating birds, forgetting which way is north.

Moreover, because the setup is in a tight corner of the building, there's no room for the tokonoma at the far end, so it's at the near end, where usually one would have the nijiriguchi entrance—so, either the first guest has to be furthest from the tokonoma or the guests sit in opposite order! This makes for a lot of adjustments in courtesy bowing and language between the guests. Good to be kept on our toes.

So, at the PMA I was thinking of tatami. The museum has quite a chanoyu collection: an entire teahouse complex, with yoritsuki (waiting room) and tearoom/pantry, connected by a garden, and side galleries with dougu and calligraphy. (Tour the collection through "A Taste for Tea" and "Sunkaraku", here.) So I headed in that direction to check out the tatami and visit the dougu.

The complex was built by the Tokyo architect OUGI Rodou (仰木魯堂, 1863–1941) for his own use, around 1917, and sold to the Museum in 1928. (Ougi built other teahouses, too, but this is the only example outside Japan.) The tearoom itself is structured as 二畳台目 nijoudaime, a two-mat room with a separate three-quarter mat (daime) for the host and brazier, divided by a semi-wall with a rustic 床柱 tokobashira post. It's named Sunkaraku-an (寸暇楽庵), "Fleeting/Evanescent Joys", after a panel that hangs over the garden side, carved by the daimyo and tea master MATSUDAIRA Harusato (1751–1818, called Fumai 不昧 "Not Dark"?). Inside the tearoom is a kakejiku donated by Ougi, "kankokka", which the Museum translates as "look to where you stand". (I can't quite read the kanji, but maybe "官刻下" or "感刻下"—"senses/present"—?) The scroll is by TAKAHASHI Yoshio, who also made some of the dougu, so maybe he and Ougi knew each other.

The complex was built by the Tokyo architect OUGI Rodou (仰木魯堂, 1863–1941) for his own use, around 1917, and sold to the Museum in 1928. (Ougi built other teahouses, too, but this is the only example outside Japan.) The tearoom itself is structured as 二畳台目 nijoudaime, a two-mat room with a separate three-quarter mat (daime) for the host and brazier, divided by a semi-wall with a rustic 床柱 tokobashira post. It's named Sunkaraku-an (寸暇楽庵), "Fleeting/Evanescent Joys", after a panel that hangs over the garden side, carved by the daimyo and tea master MATSUDAIRA Harusato (1751–1818, called Fumai 不昧 "Not Dark"?). Inside the tearoom is a kakejiku donated by Ougi, "kankokka", which the Museum translates as "look to where you stand". (I can't quite read the kanji, but maybe "官刻下" or "感刻下"—"senses/present"—?) The scroll is by TAKAHASHI Yoshio, who also made some of the dougu, so maybe he and Ougi knew each other.

At this point time was running short, so I buzzed through the dougu, tried to read the calligraphy, and took as many pictures as I could. (One shikishi really stood out, a 17th-century writing of a poem from the 11th-century Wakan Roueishuu; it's been difficult to find out much about it beyond the museum's translation, but I'll keep looking.)

On the way out, I hit the gift shop, supposing that if dougu were to be found anywhere in town it would be there. No such luck, but I did find a rack of brushes, all unique—goat, "beaver" (which 先生 says probably is tanoki), etc. One of them had a curved ox bone on the end, presumably as a hook to hang it up. I bought two: one with a bamboo shaft and black-and-white monkey fur (or so it says)—I've never tried a monkey brush, and it made me think of the colobus monkeys I like at the zoo—and another that's of goat fur, with a severe black handle that reminds me of Darth Vader. Silly, I know, but I can justify buying things from the museum because it supports a good cause.

There were, too, some other Japanese items: colorful tabi, shoes, bundles of old kimono fabric, ceramics など. There were a few general tea sets (not dougu), and one of them demanded that I take it home. It's decorated with a calligraphed poem:

Here's the fun part: the poem is by the famous (and now deified) SUGAWARA no Michizane (who also appears in the Wakan Roueishuu). What particularly amuses me about it is his name: "michi" is another reading of the "dou" in "dougu", and "zane" is only two strokes different from the "gu". So, I went to the museum looking for dougu 道具 but instead found Michizane 道真. あははは。

*The "new" Sakura Pavilion is, in fact, two single-room brick buildings built for the 1876 World's Fair that Shofuso recently acquired and renovated for classes and storage; originally they were built as "comfort stations" (i.e., 手洗い). I snuck in once, before the renovation, when the original space-architecture and plumbing fixtures all were still in place. Very different from modern public restrooms! And the gents' space was in layout very little like the ladies' space. 面白いですね。

This past Saturday, when once again I found myself at the PMA, I had two things on my mind: tea utensils (道具 dougu) and tearoom tatami layouts. Dougu, because I always think about dougu after tea; after hours of handling them and discussing them (during 拝見) it's impossible not to. Tatami configurations, because we'd just had our first class in the new Sakura Pavilion*, in which the tatami for tea practice are configured differently from the practice spaces at Shofuso itself.

| Shofuso (I think) |

At Shofuso we practice either in the shoin, a 15-mat room, or in the small chashitsu, a square format that's 4.5 mats in overall size but with an inset tokonoma that occupies one half mat in one corner. (See image at right; said to reflect the tearoom in which Rikyuu ended his life, which presumably was at Juurakudai.) The Sakura pavilion has loose tatami that can be configured however the teachers think best, so this time it was a standard four-and-a-half-mat format (below). Of course, since pretty much everything (including every step) in chanoyu is choreographed per the configuration of the tatami, the new format means recalibrating every step! Like migrating birds, forgetting which way is north.

| standard 4.5-mat format |

So, at the PMA I was thinking of tatami. The museum has quite a chanoyu collection: an entire teahouse complex, with yoritsuki (waiting room) and tearoom/pantry, connected by a garden, and side galleries with dougu and calligraphy. (Tour the collection through "A Taste for Tea" and "Sunkaraku", here.) So I headed in that direction to check out the tatami and visit the dougu.

The complex was built by the Tokyo architect OUGI Rodou (仰木魯堂, 1863–1941) for his own use, around 1917, and sold to the Museum in 1928. (Ougi built other teahouses, too, but this is the only example outside Japan.) The tearoom itself is structured as 二畳台目 nijoudaime, a two-mat room with a separate three-quarter mat (daime) for the host and brazier, divided by a semi-wall with a rustic 床柱 tokobashira post. It's named Sunkaraku-an (寸暇楽庵), "Fleeting/Evanescent Joys", after a panel that hangs over the garden side, carved by the daimyo and tea master MATSUDAIRA Harusato (1751–1818, called Fumai 不昧 "Not Dark"?). Inside the tearoom is a kakejiku donated by Ougi, "kankokka", which the Museum translates as "look to where you stand". (I can't quite read the kanji, but maybe "官刻下" or "感刻下"—"senses/present"—?) The scroll is by TAKAHASHI Yoshio, who also made some of the dougu, so maybe he and Ougi knew each other.

The complex was built by the Tokyo architect OUGI Rodou (仰木魯堂, 1863–1941) for his own use, around 1917, and sold to the Museum in 1928. (Ougi built other teahouses, too, but this is the only example outside Japan.) The tearoom itself is structured as 二畳台目 nijoudaime, a two-mat room with a separate three-quarter mat (daime) for the host and brazier, divided by a semi-wall with a rustic 床柱 tokobashira post. It's named Sunkaraku-an (寸暇楽庵), "Fleeting/Evanescent Joys", after a panel that hangs over the garden side, carved by the daimyo and tea master MATSUDAIRA Harusato (1751–1818, called Fumai 不昧 "Not Dark"?). Inside the tearoom is a kakejiku donated by Ougi, "kankokka", which the Museum translates as "look to where you stand". (I can't quite read the kanji, but maybe "官刻下" or "感刻下"—"senses/present"—?) The scroll is by TAKAHASHI Yoshio, who also made some of the dougu, so maybe he and Ougi knew each other.At this point time was running short, so I buzzed through the dougu, tried to read the calligraphy, and took as many pictures as I could. (One shikishi really stood out, a 17th-century writing of a poem from the 11th-century Wakan Roueishuu; it's been difficult to find out much about it beyond the museum's translation, but I'll keep looking.)

On the way out, I hit the gift shop, supposing that if dougu were to be found anywhere in town it would be there. No such luck, but I did find a rack of brushes, all unique—goat, "beaver" (which 先生 says probably is tanoki), etc. One of them had a curved ox bone on the end, presumably as a hook to hang it up. I bought two: one with a bamboo shaft and black-and-white monkey fur (or so it says)—I've never tried a monkey brush, and it made me think of the colobus monkeys I like at the zoo—and another that's of goat fur, with a severe black handle that reminds me of Darth Vader. Silly, I know, but I can justify buying things from the museum because it supports a good cause.

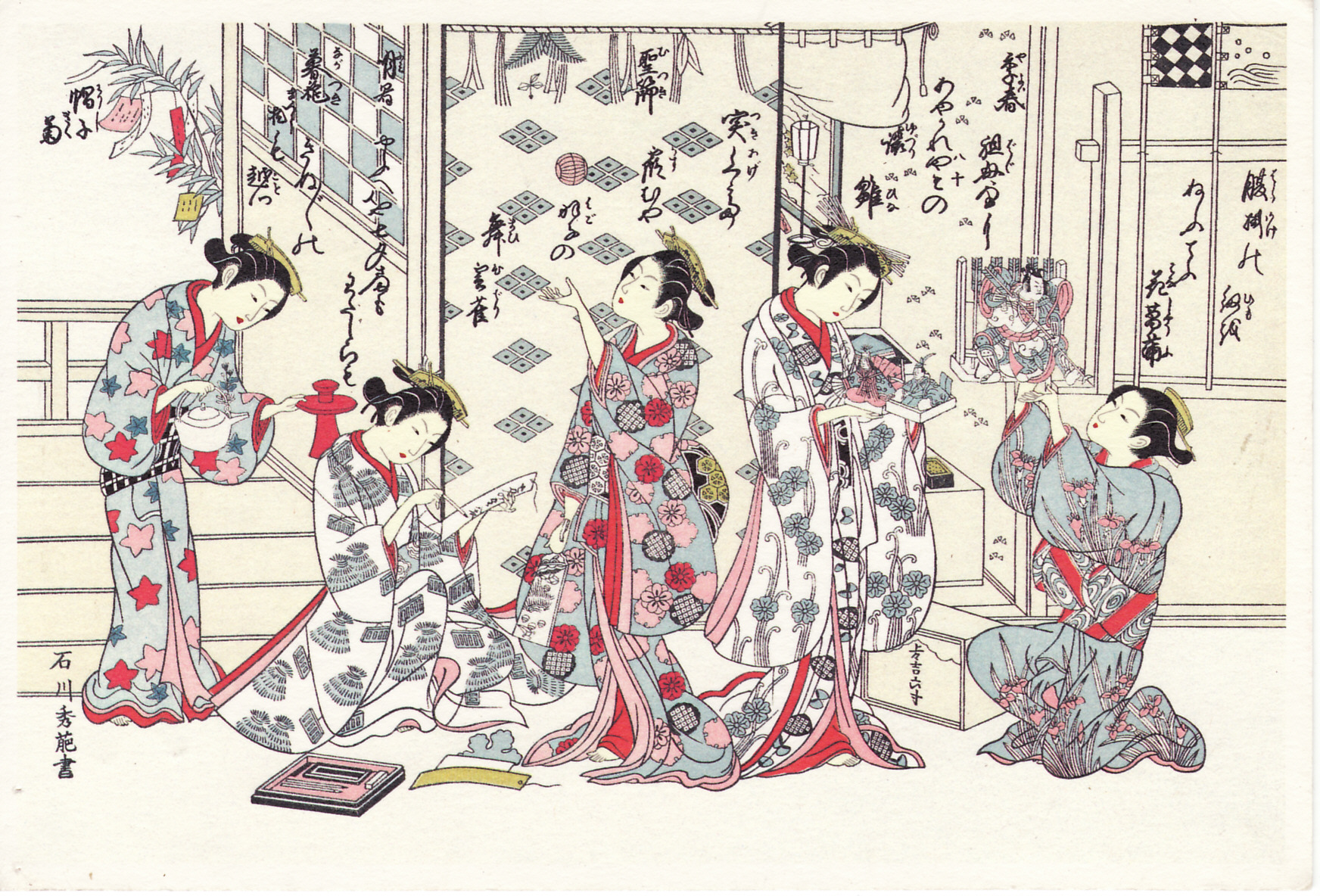

There were, too, some other Japanese items: colorful tabi, shoes, bundles of old kimono fabric, ceramics など. There were a few general tea sets (not dougu), and one of them demanded that I take it home. It's decorated with a calligraphed poem:

東風吹かばIt made me happy, because it's fun to try to read the writing, and 忘れぞ (忘るな) is like the tanka we're working on now, 忘れし—the same idea of (not) forgetting. "The eastern breeze blows and brings spring fragrance; plum blossoms, even though your master isn't around, don't forget to spread your fragrance." Or something. I've read that 匂い has an older sense that's not about scents. おこせよ is probably some kind of awakening (起こす). The last three words were modified in a later collection—almost two centuries later, that is—as 春を忘るな, which makes sense as "don't forget spring". Apparently when the poet was exiled from Kyouto he missed his plum tree so much that it was dug up and taken to him. (There are 6,000 plum trees at the shrine to him in Fukuoka, including the "flying plum" 飛梅 that's said to have flown to him on its own.) Some of the writing on the tea set is a little weird, so 先生 says it probably was written phonetically. I like it, though, and am glad to have met it.

にほひおこせよ

梅の花

主なしとて

春な忘れぞ

kochi fukaba

nioi okoseyo

ume no hana

aruji nashi tote

haru na wasure zo

Here's the fun part: the poem is by the famous (and now deified) SUGAWARA no Michizane (who also appears in the Wakan Roueishuu). What particularly amuses me about it is his name: "michi" is another reading of the "dou" in "dougu", and "zane" is only two strokes different from the "gu". So, I went to the museum looking for dougu 道具 but instead found Michizane 道真. あははは。

*The "new" Sakura Pavilion is, in fact, two single-room brick buildings built for the 1876 World's Fair that Shofuso recently acquired and renovated for classes and storage; originally they were built as "comfort stations" (i.e., 手洗い). I snuck in once, before the renovation, when the original space-architecture and plumbing fixtures all were still in place. Very different from modern public restrooms! And the gents' space was in layout very little like the ladies' space. 面白いですね。

Wednesday, July 18, 2012

Haiku contest!

「上級へのとびら」という教科書は、生徒が勉強できるためのサイトがあります。今日サイトに行って、俳句・川柳のコンテストがあるのを覚えました。(「見ました」?「聞き及びました」?「見及びました」?そのような動詞、あるだろうと思いますが。) だから、俳句を作って、提出してみるのが面白いかもしれませんね。今晩日本語のレッスンがあるので、先生に相談しようと思っています。茶の湯の虫についての俳句は、下手すぎますかなぁ。 あとは—?

Earlier today I was reading the Tobira textbook and visited its website for students (which is replete with awesomeness), and I noticed a nav item about haiku. Turns out they're having a haiku contest! It would be fun to try to compose one, just for the heck of it.* Maybe I should send that one from tea class about the fly, but it's hard to tell whether the grammar, etc., is OK. Probably not. I could change 様 to さん without affecting the mora count. I'll talk with 日本語の先生 about it this evening.

(Funny that I sometimes have to think about "writing" a poem, vs "composing"; in shuuji we write 書 poems, but not poems we composed 作! 習字のレッスンではよく句を書いてみますが、自分の作った句じゃないんですよ。。。。)

*"For the heck of it" reminds me that I've never found a satisfactory Japanese equivalent for the English "why not?". It's a very important phrase! "Why would you want to send in a haiku?" "Why not?"

Earlier today I was reading the Tobira textbook and visited its website for students (which is replete with awesomeness), and I noticed a nav item about haiku. Turns out they're having a haiku contest! It would be fun to try to compose one, just for the heck of it.* Maybe I should send that one from tea class about the fly, but it's hard to tell whether the grammar, etc., is OK. Probably not. I could change 様 to さん without affecting the mora count. I'll talk with 日本語の先生 about it this evening.

(Funny that I sometimes have to think about "writing" a poem, vs "composing"; in shuuji we write 書 poems, but not poems we composed 作! 習字のレッスンではよく句を書いてみますが、自分の作った句じゃないんですよ。。。。)

*"For the heck of it" reminds me that I've never found a satisfactory Japanese equivalent for the English "why not?". It's a very important phrase! "Why would you want to send in a haiku?" "Why not?"

Tuesday, July 17, 2012

久しくも。。。。 (Cicadas for summer.)

今の夏についての短歌は、これです:

久しくも hisashiku moOr something along those lines. I like that that structure in English has some ambiguity, between "the chirping of the cidada" and "the cicada is chirping" (鳴き出でにけり). The けり ending suggests continuity, like the waves of cicada song one hears in the woods on a summer night. It's by KUBOTA (窪田空穂, 1877–1967), a poet and literary scholar from Nagawa (formerly Wada), Matsumoto, Nagano, and the more I write it, the more I like it. (Amazingly, the poem isn't googleable, so, here: 久しくも聞かざるからにそのあるを忘れし蝉の鳴きいでにけり. Now it is.)

聞かざるからに kikazaru kara ni

そのあるを sono aru o

忘れし蝉の wasureshi semi no

鳴きいでにけり naki ide ni keri

the cicada's chirping—so long since I've heard it, I'd forgotten

We chose some hentaigana—fun to try different combinations!—and historical models for the kanji, and now we're working on the whole thing in chirashi, something like this:

蝉

|

|||||||||

の

|

曽

|

||||||||

鳴

|

の

|

聞

|

|||||||

支

|

阿

|

可

|

|||||||

い

|

留

|

沙

|

久

|

||||||

て

|

を

|

留

|

し

|

||||||

爾

|

忘

|

か

|

具

|

||||||

希

|

れ

|

ら

|

母

|

||||||

り

|

し

|

二

|

|||||||

Really fun to write, especially since it has several characters I particularly like: 母(も), 聞, 沙,ら,曽(そ),忘,支,爾(に), and especially 希(け), which starts like a little swordfight and ends with the wrap-and-pull action that's so much fun in ゆ.Certainly not without its challenges, though; I'm not very good with the sliding of し, and I find some of the other shapes really difficult—not to mention spacing, chirashi, etc., etc.... でも、いつものように、頑張りましょうね。

Corrections: (1) accidentally had 着 instead of 聞; still need to fix 沙.

Monday, July 9, 2012

Tanabata tea; making dougu?

|

| Tanabata in Edo, by Hiroshige |

|

| kuro-raku |

*Agar-agar is great for tea sweets, but you can also use it to culture bacteria, run polymerase chain reactions, house ants in an ant farm, make dental impressions, and, probably, to clean windows and ovens. There's nothing it can't do!

Friday, July 6, 2012

茶会! (In which we meet for tea.)

Attended a very special 茶会 tea gathering yesterday, the first official chakai in a friend's 茶室 tearoom in her home. It's a two-mat room; our hostess told us this was the last style of tearoom that Rikyuu built, and it's easy to see why—so intimate (and efficient)! We did the whole thing, from washing at the 手水鉢 chouzubachi through koicha and usucha. We started off with an amazing meal together in the tearoom—marinated salmon with toasted nori, taro root and stems, a rice cake with greens and edamame, a dish of pickled items (including daikon and a really interesting ginger flower), miso soup with fiddlefern heads, and delicious cold osake, which was perfect for a hot July day. 超美味しかったよ。 本当にご馳走様でした。 We finished the meal with blueberries in cool, clear agar-agar (an algae-based gelatin that functions as Jello but without the hooves)—incredibly yummy. So much work for our hostess!

We retired to the machiai to relax and chat a bit before koicha; then back into the 茶室 for koicha and then usucha. The first 茶碗 tea bowl was dark and friendly, and the viscous green residue of the koicha contrasted beautifully with the dark glaze, like a deep forest when the trees are wet. (Our hostess told us that Rikyuu liked dark bowls for exactly that contrast.) The second was much lighter and had a special property of "blooms"—some kind of microbe embedded in the bowl that expands colorfully in reaction to hot water (and then shrinks again as the bowl cools). For koicha the 茶入れ chaire was also of a rich, darkish glaze, with a very helpful drip to tell us which end was the front. :-) (This is important because things always have to face the right way, and the right way tends to vary. A lot.) The 仕覆 shifuku (cloth container) for the chaire was of a bright gold stitching on lighter background, almost a brocade, and, with its darker cord, had a funny way of, when laid on the floor, actually looking like a teapot. I think the name for this style is 茶筅飾り, but really it was to honor first use of one of our hostess's 水差し misuzashi, a portly ocean-blue guy perfect for summer. In the tokonoma, a shikishi of 薫風, a warm summer/fragrant breeze, and thyme from the garden for fragrance. Truly, a great pleasure, and a great honor to be 正客 first guest, even though I'm not very good at it. へへへ

This morning I tried to write a few new things, just for fun. 四字熟語 four-kanji idioms and things appropriate for tea—和敬清寂 and 喫茶去—and some other things that I just like, like 順風満帆 ("fortuitous wind, full sails", which always makes me happy), 七転び八起き ("seven times falling, eight times rising"), and of course 酔生夢死. My writing was egregious, even by my own low standards, so I'm glad that Tanabata is coming up so I can wish for better writing. 今晩の七夕祭りのための特別な茶会、本当に楽しみにしていますよ。

(特別の。。。特別な。。。どちらがいいかなぁ。。。)

We retired to the machiai to relax and chat a bit before koicha; then back into the 茶室 for koicha and then usucha. The first 茶碗 tea bowl was dark and friendly, and the viscous green residue of the koicha contrasted beautifully with the dark glaze, like a deep forest when the trees are wet. (Our hostess told us that Rikyuu liked dark bowls for exactly that contrast.) The second was much lighter and had a special property of "blooms"—some kind of microbe embedded in the bowl that expands colorfully in reaction to hot water (and then shrinks again as the bowl cools). For koicha the 茶入れ chaire was also of a rich, darkish glaze, with a very helpful drip to tell us which end was the front. :-) (This is important because things always have to face the right way, and the right way tends to vary. A lot.) The 仕覆 shifuku (cloth container) for the chaire was of a bright gold stitching on lighter background, almost a brocade, and, with its darker cord, had a funny way of, when laid on the floor, actually looking like a teapot. I think the name for this style is 茶筅飾り, but really it was to honor first use of one of our hostess's 水差し misuzashi, a portly ocean-blue guy perfect for summer. In the tokonoma, a shikishi of 薫風, a warm summer/fragrant breeze, and thyme from the garden for fragrance. Truly, a great pleasure, and a great honor to be 正客 first guest, even though I'm not very good at it. へへへ

This morning I tried to write a few new things, just for fun. 四字熟語 four-kanji idioms and things appropriate for tea—和敬清寂 and 喫茶去—and some other things that I just like, like 順風満帆 ("fortuitous wind, full sails", which always makes me happy), 七転び八起き ("seven times falling, eight times rising"), and of course 酔生夢死. My writing was egregious, even by my own low standards, so I'm glad that Tanabata is coming up so I can wish for better writing. 今晩の七夕祭りのための特別な茶会、本当に楽しみにしていますよ。

(特別の。。。特別な。。。どちらがいいかなぁ。。。)

Wednesday, July 4, 2012

Happy Fourth!

It's Independence Day here in the US, the day on which we both perpetrate and endure many platitudes about democracy while in fact we continue to erode politically the very cultural narrative (populism, progress, pursuit of happiness) that the holiday is meant to celebrate. Just sayin'. But happy Fourth! 今晩は花火ですね—"fire flowers" this evening. Tomorrow tea practice with a friend and, later, 日本語のレッスン, and then on Friday 休み and then Tanabata 七夕祭り in Fairmount Park. Hopefully, tea class on Saturday and 習字 on Saturday or Sunday. Then, on the 14th, Bastille Day, which we celebrate with much enthusiasm here in Philadelphia (which considers itself the "sister city" to Paris; our own Ben Franklin was ambassador and, it seems, rather a rake).* A good time will, undoubtedly, be had by all. 夏の祭りは大変楽しいと思いますね。酷く楽しいでしょうね。(笑) ガハハ

今朝習字を練習してみましたよ。 I did some writing practice this morning, first 俳句 and 習字 (行書で「澄懐」) and then, in honor of the day, 独立 (dokuritsu, "independence" but, more literally, "standing alone"**) and 自由 (jiyuu, "liberty", but because it derives from 自 self + 由 rationale I like to think of it as "thinking/choosing for oneself"). My holiday writing wasn't very good, but I'm giving myself a by for household ephemera. (Is "give a by" the phrase? 英語はアメリカ人にもときどきちょっと難しいと思いますね.***)

Tonight in theory I am at an event but really I'd rather continue trying to read and translate the rest of the summer haiku from 「俳句編」.

I discovered today that we have a giant Asian grocery store right here in Center City—which is great because it means I can get some things I need for tea without taking buses or trains. I was looking for wagashi for tea tomorrow, and though I didn't find what I really wanted (artisanal wagashi—not likely this side of New York), I found some 良さそうな抹茶, macha that looks like it'll work at least for usucha, and then various okashi and lots of random things that I'm just looking forward to exploring. (I've never in my life had an entire fish in my freezer, but a milkfish resides there now.)

本当に夏になっていますね。

*The tradition here for the Quatorze is to have someone dress as Marie-Antoinette and toss Twinkies or some substitute ("qu'ils mangent de la brioche", which probably she did not in fact say) from the ramparts of Eastern State Penitentiary, which is the closest building we have to the Bastille.

**ですが。。。「独」というのはね。Per Henshall, 独 derives from kemono-hen, the (wild) dog radical, and a caterpillar, formerly written as 属 (and older forms) but now written as the indefatigable mushi 虫, generic insectness. Dog and caterpillar together came to mean unity, fighting for a single cause (which would be what, exactly?) and then, eventually, singularity. It also means Germany; I can't even begin to engage that.

***In saying this I'm making a reference to an interesting point that bikenglishさん made in his blog, about problems with prepositions when they refer to unusual physical situations—behind the yellow line? below it? beneath it? In the train, or on it? (When I was studying literary critical theory we'd have thought of it as intertextuality.) Last week at 習字 we read a little from the 古今和歌集, to practice reading hentaigana, so since then I've been thinking about 本歌取り honkadori, the poetic practice of alluding to a classical poem, in order to both demonstrate erudition and link one's own work to a larger tradition. I wrote something about it, I think, involving Sosei and 袖ひちて むすびし水の こほれるを 春立つ今日の 風やとくらむ dipping kimono sleeves in freezing water and 春たてば 花とやみらん白雪の かゝれる枝に うぐひすのなく nightingales on branches in the remaining spring snow, and Princess Shikishi waiting in vain for her lover, but it seems that I now have more drafts than actual posts. Story of my life!

今朝習字を練習してみましたよ。 I did some writing practice this morning, first 俳句 and 習字 (行書で「澄懐」) and then, in honor of the day, 独立 (dokuritsu, "independence" but, more literally, "standing alone"**) and 自由 (jiyuu, "liberty", but because it derives from 自 self + 由 rationale I like to think of it as "thinking/choosing for oneself"). My holiday writing wasn't very good, but I'm giving myself a by for household ephemera. (Is "give a by" the phrase? 英語はアメリカ人にもときどきちょっと難しいと思いますね.***)

Tonight in theory I am at an event but really I'd rather continue trying to read and translate the rest of the summer haiku from 「俳句編」.

I discovered today that we have a giant Asian grocery store right here in Center City—which is great because it means I can get some things I need for tea without taking buses or trains. I was looking for wagashi for tea tomorrow, and though I didn't find what I really wanted (artisanal wagashi—not likely this side of New York), I found some 良さそうな抹茶, macha that looks like it'll work at least for usucha, and then various okashi and lots of random things that I'm just looking forward to exploring. (I've never in my life had an entire fish in my freezer, but a milkfish resides there now.)

本当に夏になっていますね。

*The tradition here for the Quatorze is to have someone dress as Marie-Antoinette and toss Twinkies or some substitute ("qu'ils mangent de la brioche", which probably she did not in fact say) from the ramparts of Eastern State Penitentiary, which is the closest building we have to the Bastille.

**ですが。。。「独」というのはね。Per Henshall, 独 derives from kemono-hen, the (wild) dog radical, and a caterpillar, formerly written as 属 (and older forms) but now written as the indefatigable mushi 虫, generic insectness. Dog and caterpillar together came to mean unity, fighting for a single cause (which would be what, exactly?) and then, eventually, singularity. It also means Germany; I can't even begin to engage that.

***In saying this I'm making a reference to an interesting point that bikenglishさん made in his blog, about problems with prepositions when they refer to unusual physical situations—behind the yellow line? below it? beneath it? In the train, or on it? (When I was studying literary critical theory we'd have thought of it as intertextuality.) Last week at 習字 we read a little from the 古今和歌集, to practice reading hentaigana, so since then I've been thinking about 本歌取り honkadori, the poetic practice of alluding to a classical poem, in order to both demonstrate erudition and link one's own work to a larger tradition. I wrote something about it, I think, involving Sosei and 袖ひちて むすびし水の こほれるを 春立つ今日の 風やとくらむ dipping kimono sleeves in freezing water and 春たてば 花とやみらん白雪の かゝれる枝に うぐひすのなく nightingales on branches in the remaining spring snow, and Princess Shikishi waiting in vain for her lover, but it seems that I now have more drafts than actual posts. Story of my life!

Sunday, July 1, 2012

Haiku; Ootsubukuro (repaired).

(Blogger decided to delete this one. Yay.)

I don't know why I have haiku on the brain these days, but I do. Yesterday at tea class, we could hear a waterfall in the pond and a frog croaking, so, naturally,

Anyway. In tea class yesterday we did usucha and then koicha, a new-to-me temae called Ootsubukuro in which the natsume is wrapped in not the fukusa but a bag similar to bags formerly used to carry grain from Ootsu to Kyouto (about 7 miles away). Apparently Rikyuu's wife made the first Ootsubukuro and Rikyuu developed the style. Me, I'm eagerly awaiting 洗い茶巾 araijakin season (July and August); the temae that emphasizes the sound of water—beautiful, and perfect for the summer.

I don't know why I have haiku on the brain these days, but I do. Yesterday at tea class, we could hear a waterfall in the pond and a frog croaking, so, naturally,

古池 / 蛙飛び込む / 水の音And when a fly buzzed in cavalierly and circled the tray of お菓子 tea sweets,

furu ike ni kawazu tobikomu mizu no oto

Into the old pond the frog jumps—sound of the water (or: splash!)

Bashou, 1686

塗盆を蝿が雪隠にしたりけりAnd then, when as I was walking home it rained on me,

nuribon o hae ga secchin ni shitari keri

the fly makes the lacquer tray a bathroom

Issa, 1824

着ながらにせんだくしたり夏の雨This morning when I came downstairs I met a cockroach, who was investigating the running clothes that I'd thrown on the floor yesterday. (My house is 200+ years old, so such encounters do happen from time to time.) He perked up when I entered the room, and then we looked at each other for a few seconds; then I picked up a binder of legal opinions that happened to be nearby and smashed him. As I learned yesterday, Issa, who practiced 浄土仏教 "Pure Land" Buddhism, also thought about the ethics of killing insects:

kinagara ni sentaku shitari natsu no ame

washing my clothes while wearing them—summer rain

Issa, 1821

蝿打てけふも聞也山の鐘In fact Issa wrote quite a few poems about swatting things. (Then again, as Issa wrote about 20,000 haiku, there probably are quite a few about anything!)

hae uchite kefu (kyou) mo kikunari yama no kane

swatting a fly, today again I hear the mountain (temple) bell

1806

蠅打に敲かれ玉ふ仏哉

hae uchi ni tatakare tamau hotoke kana

in swatting a fly, hitting the Buddha

1808

蝿一つ打てはなむあみだ仏哉

hae hitotsu utte wa namu amida butsu kana

swatting a single fly—praise to Amida Buddha!

1814

蝿打やあみだ如来の御天窓

hae utsu ya amida nyorai no onatama

swatting a fly—Amida Buddha's holy head

1815

(D Lanoue's translation of "holy head"; 御天窓 might also be otenmado, but I'm sure it has specific meanings and he's reading it correctly.)

やれ打な蝿が手をすり足をする

yare utsuna hae ga te wo suriashi o suru

don't swat the fly! he's rubbing his feet together [as if in prayer]

1821

Anyway. In tea class yesterday we did usucha and then koicha, a new-to-me temae called Ootsubukuro in which the natsume is wrapped in not the fukusa but a bag similar to bags formerly used to carry grain from Ootsu to Kyouto (about 7 miles away). Apparently Rikyuu's wife made the first Ootsubukuro and Rikyuu developed the style. Me, I'm eagerly awaiting 洗い茶巾 araijakin season (July and August); the temae that emphasizes the sound of water—beautiful, and perfect for the summer.

蝿; 挨拶.

So yesterday, when that fly appeared and buzzed around the tea sweets, I made up a lame haiku about it:

Aisatsu is the formal bow/greeting before tea class, in which one asks the teacher for a lesson (and the guests for their patience). It's done when one has barely entered the room, when the feet are just past the threshold. The fukusa isn't yet tucked into the obi, because it's possible that the teacher will decline to give you a lesson; only if the teacher agrees can you return to the mizuya and gear up to make tea.

The fly entered the room without aisatsu, so no sweets for him!

蝿様もお菓子の前に挨拶ね(I'm pretty sure the grammar is wrong, but it's tough with haiku, and anyway that's what occurred to me.)

hae sama mo okashi no mae ni aisatsu ne

even for you, Lord Fly, before the sweets, aisatsu

Aisatsu is the formal bow/greeting before tea class, in which one asks the teacher for a lesson (and the guests for their patience). It's done when one has barely entered the room, when the feet are just past the threshold. The fukusa isn't yet tucked into the obi, because it's possible that the teacher will decline to give you a lesson; only if the teacher agrees can you return to the mizuya and gear up to make tea.

The fly entered the room without aisatsu, so no sweets for him!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)