Tuesday, December 31, 2019

書き初め!

Thursday, December 26, 2019

Tuesday, December 17, 2019

嘗て。

かつて。That's a new one. I've been encountering lots and lots of vocab that's new to me, but you'd think, in studying 短歌 (tanka) and 昔話 (folk tales), I'd have some across かつて somewhere. Once, used to be. (The classic start to a folk tale is 昔々, mukashi mukashi, equivalent to once upon a time—different sense of once? I do see examples of it as interchangeable with 昔. かつては、ここに教会があった。There used to be a church here.) Apparently, with a negative verb it can refer to something that hasn't happened yet, never has, I guess as もう can. かつて僕のだった、これ。これはかつて僕のじゃない? I have seen (negative) かつてない; Weblio.jp says for katsute nai, 「今までにない、過去に前例がない、といった意味の言い回し」—not up to now, not so far, no such precedent.

From 嘗て. Henshall doesn't list the kanji; the MS IME does substitute 嘗 for かつ in "かつて". Variant kanji is 甞. katsute 嘗て, nameru, kokoromiru... なめる and licking? To be followed up on, sometime when it's not (already) almost 7am...

Wednesday, December 11, 2019

会社で働くのは、frei macht か。

Monday, December 2, 2019

Who left the light in (the branch)?

| 一枝に | hito eda ni | in one branch |

| 光のこして | hikari nokoshite | light remains |

| 里の春 | sato no haru | spring in the village (back home) |

The straightforward reading is that (sun)light just remains, but shifting to transitive—what?—implies a subject, someone who is leaving the light there? Certainly, a new way of looking at the poem.

Proverb:

虎は死して皮を留め

人は死して名を残す

tora ha shishite, kawa o todome;

hito ha shishite, na o nokosua tiger dies and leaves its skin;

a person dies and leaves their name (o nokosu)

The person (人) leaves (残す) the object (名を).

を vs が: "結果だけが残る!!!"

—only the results/consequences remain (ga nokoru)!

That light, in that one branch—has someone left it there?

才, 材, オ.

才, 材. オ. 歳.

才能, 才気, 才女, 才子, 才人, 才覚, 才力. 財 (which Henshall says a bit dubiously is composed of both shells/money 貝 and, ideographically and phonetically, a dam 才).

Talent meets age. Maybe in this case of age it's just a tl;dw ("too long; didn't write") form of 歳, with the cross-stroke recalling 戈 (and maybe 矛). Or is there a connection between age/experience and increasing aptitude/capability?

Talent meets age. Maybe in this case of age it's just a tl;dw ("too long; didn't write") form of 歳, with the cross-stroke recalling 戈 (and maybe 矛). Or is there a connection between age/experience and increasing aptitude/capability?

Of course, similarity in structure, appearance, feel, or sound doesn't necessarily mean any type of thing.

(The image is of spears/pikes 矛, from the Shimane Museum of Ancient Izumo 島根県・立古代・出雲・歴史・博物館. 才, 弋, and 矛 all seem to involve weaponry, be it spears, halberds, or bows.)

才弾ける? (a snapping string? 琴を弾く? 引く? 弾ける? 弾傷?)

Will have to suss out all this.

(Learning a lot from Duolingo and spending a lot of time asking questions on the message boards there. Doesn't hold a candle to studying with 先生, but better to stay engaged than not to!)

Monday, November 25, 2019

死亡 、希望。

Tuesday, July 23, 2019

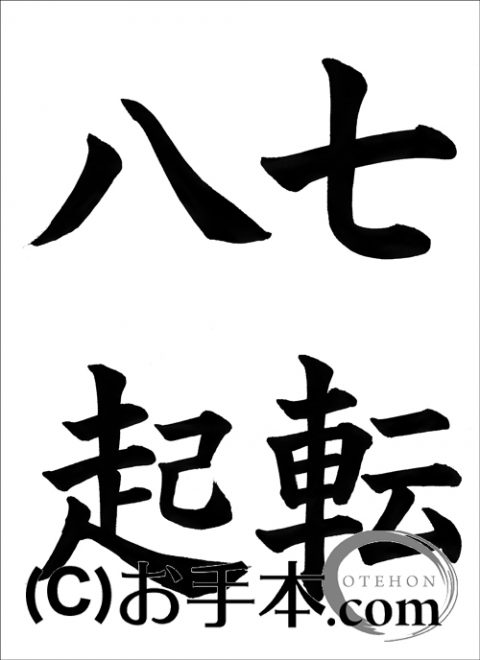

七転八起! (or, never say die!)

A thing I like a lot about learning kanji is the intersections of their meanings. In this case, we have 起, which I first learned as okiru/okosu, in the sense of awakening / getting out of bed or "knocking someone up"—i.e., awakening someone. Here, it's literally to rise after falling.

I've done a lot of falling down for a long time now and am in the process of getting up, so it seems appropriate. Shichi and hachi both are relatively simple—and hachi, of course, is of particular significance to me—so they have to be really right.

Examples below—thoughts? #八Rising

(Note: Work in progress; images are coded to link through to the source, but I'll have to fix. I'll look through them all after a nap; better just to post what I have, as I have dozens of drafts never finished!)